(This piece is meant to touch on some of the unique features of the region as an economic actor. For simplicity, I’m only using limited data. Any opinions here are my own and don’t reflect anyone else’s.)

South Asia has long been considered more a geopolitical region than an economic one. Historically, this does make sense, being halfway between the sea trade lines between the East and the West. Yet this itself points towards a more economic role as well, and one that affects South Asia overall different compared to other regions.

Yet the idea of South Asia as economically distinct is still not the most common one. It is so uncommon, that even defining what makes South Asia economically distinct itself is hard to pinpoint. In this piece, I’m attempting to lay out a few specific aspects that I feel makes South Asia’s economy unique and a little bit of hypothesizing about this as well.

South Asia’s massive (yet small) consuming population

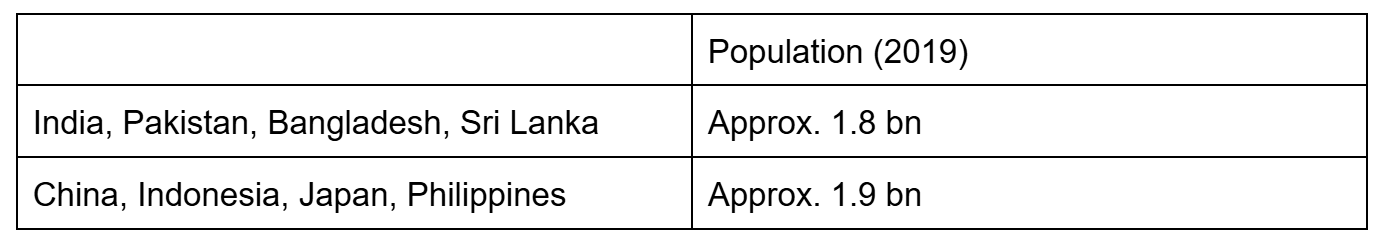

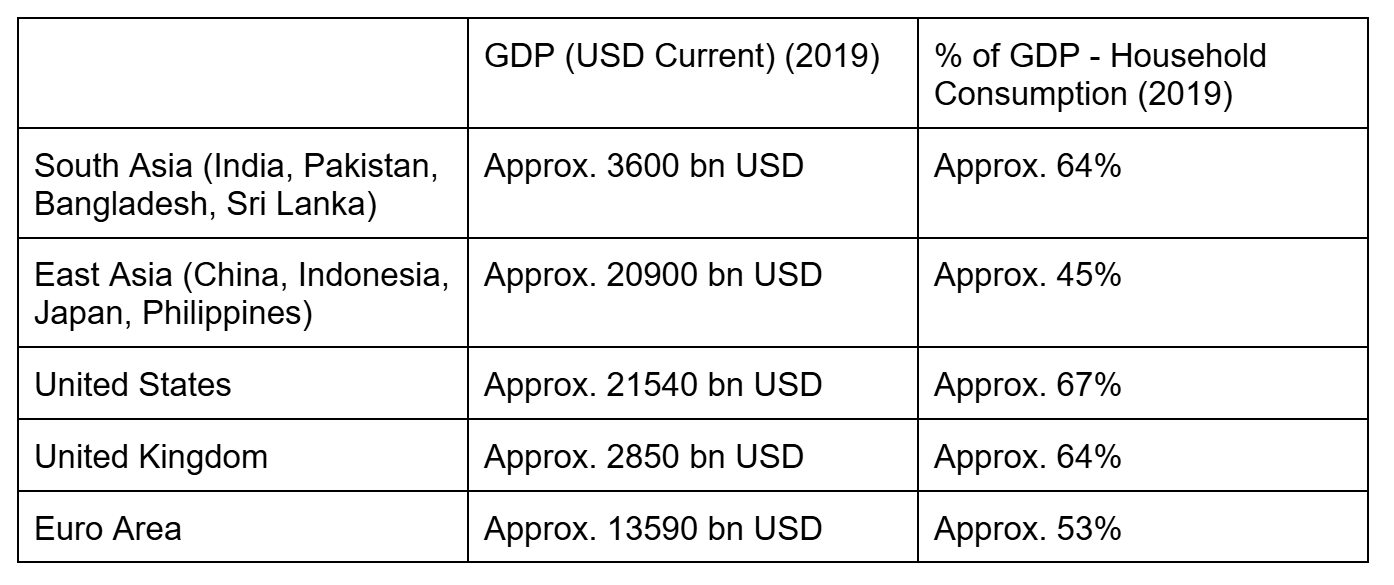

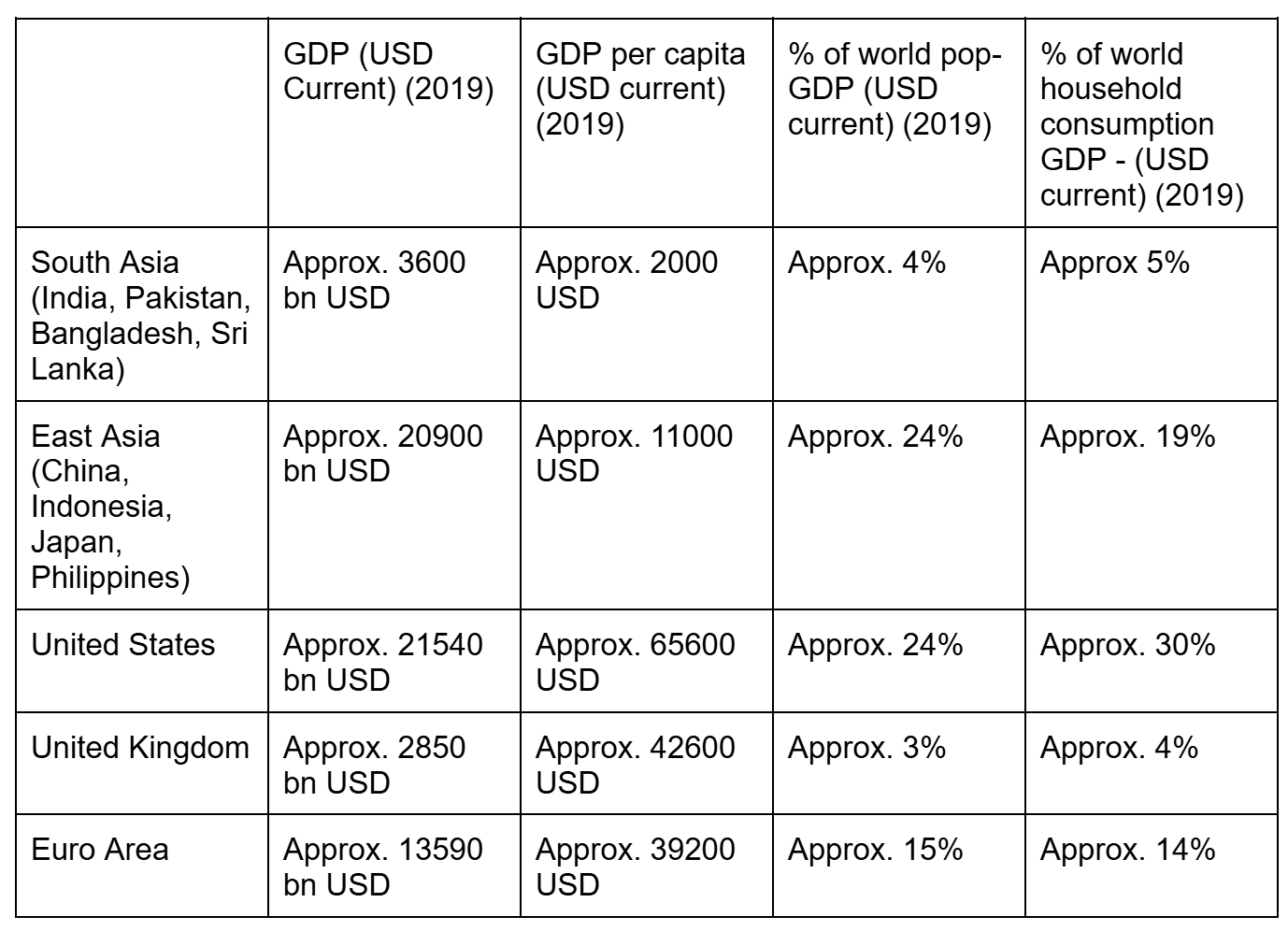

Arguably the most important point here in my view is that South Asia has a massive population, even if it is not a population that is as large as that of East Asia. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka combined hold only around 1.8 bn people, where China, Indonesia, Japan, and the Philippines alone can match that. But it is quite large nevertheless.

However, the difference between these two regions, is that South Asia’s people consume more than they produce, while the opposite is true for East Asia. South Asian households consume 64% of GDP, while East Asian households only consume 45% of GDP. In fact, South Asia’s consumption is more comparable to the US and the UK - high consumer economies, whereas East Asia is more comparable to the production centres of the Euro Area.

Despite this, South Asia is still substantially poorer than all of these regions. While it overperforms in terms of how much consumption it does compared to the size of its population, at the end of the day, it remains quite poor.

South Asia’s continuous external deficits

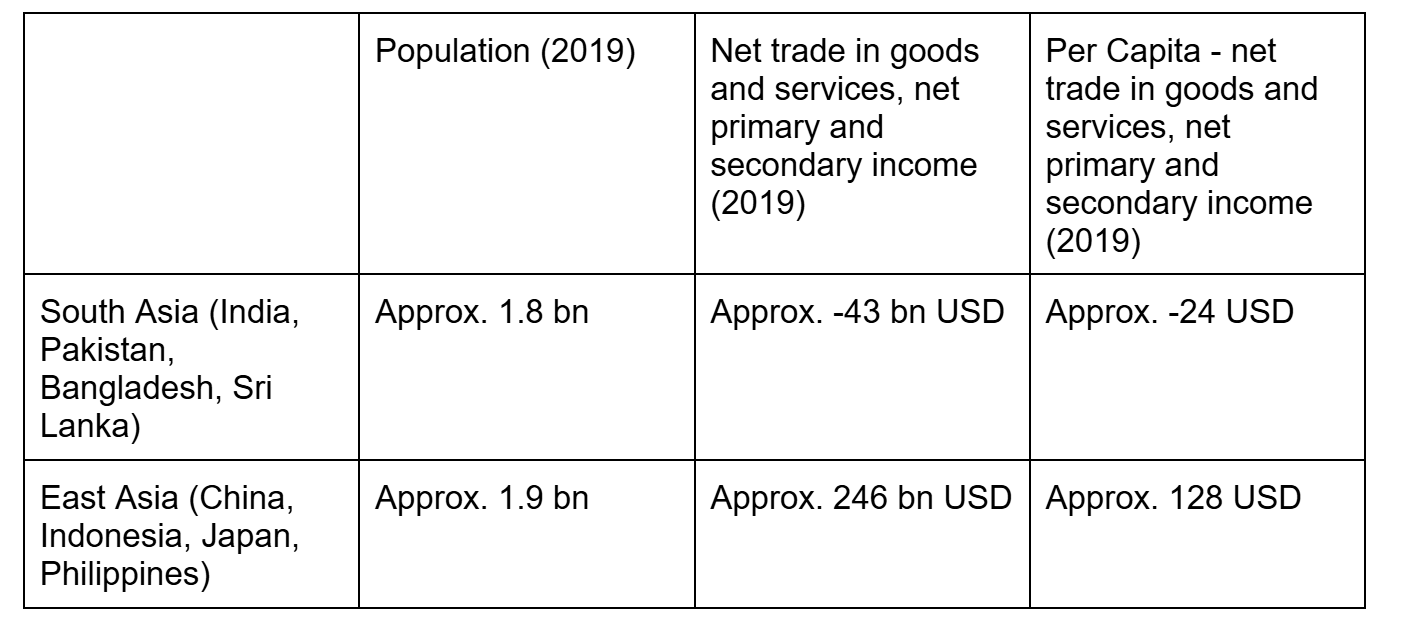

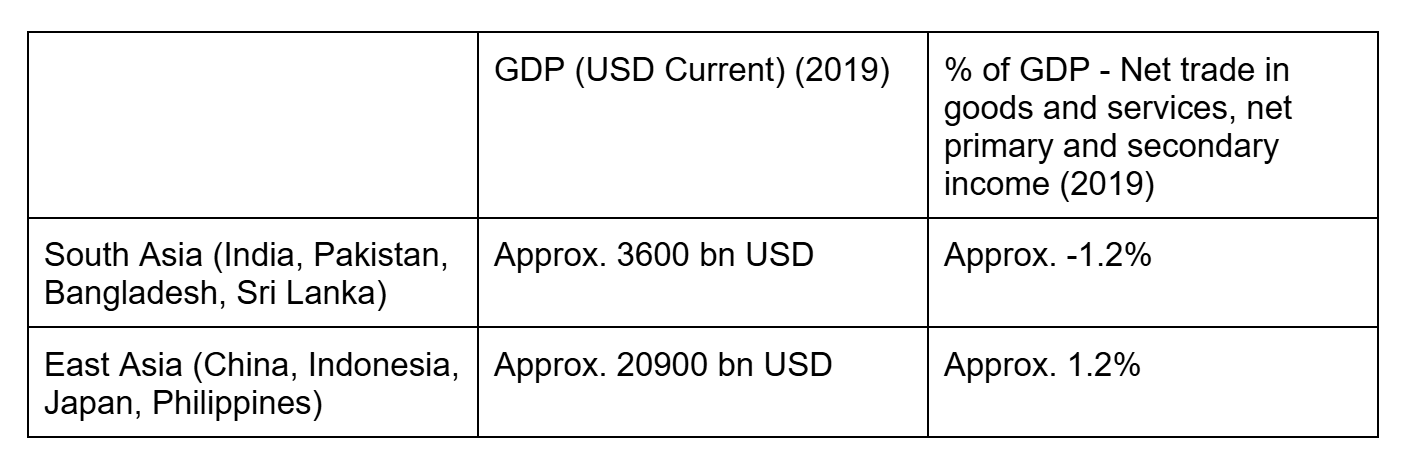

This then extends into your FX requirements. In 2019, for the countries above, you had approximately USD 100 per capita more in net exports and income in East Asia compared to South Asia. The specific balances are different, and not all countries fit the regional structure perfectly, but the overall story still remains.

This is even more true when you look at net trade and income as a proportion of these countries’ GDP - South Asia’s deficit is as large a component of its economy as East Asia’s surplus.

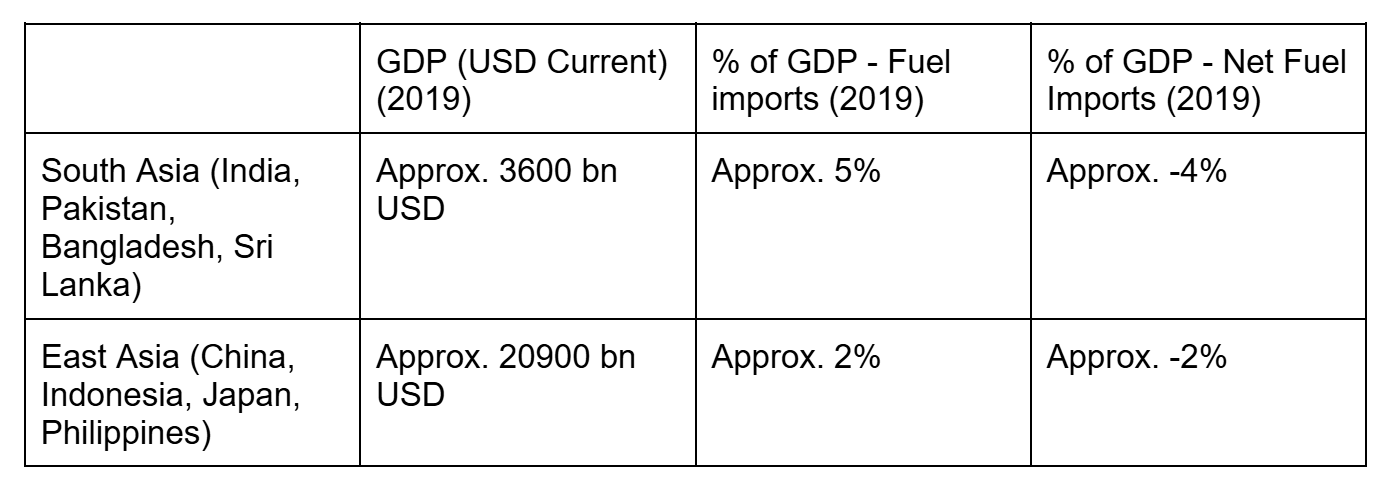

Alongside this, South Asia has very few commodity exports - which puts it apart from Latin America, Sub Saharan Africa, and even East Asia. We can see part of this by looking at fuel imports from the two regions against their GDP. South Asia imports more than twice the fuel that East Asia does as a % of its GDP. The region is also a net importer of fuel at twice the rate that East Asia is.

South Asia’s weak fiscal base

(South Asia’s fiscal picture is a much bigger story I want to expand in the future, so I’m keeping this relatively short here)

Part of which allows for all this consumption and external imports, is that South Asia’s governments have moved towards smaller and smaller tax collection over time. Tax collection has been below 13% of GDP for India and Bangladesh for a while, while Sri Lanka and Pakistan has seen consistent falls in its tax receipts. Overall revenue is only slightly better than this.

In fact, by 2019, South Asia’s tax revenue numbers looked closer to East Asia’s (where low taxes and low expenditure have gone alongside a production economy) or even lower, and were lower than most of Sub-Saharan Africa’s (commodity exporters with a significantly portioned off export sector). For how low South Asia’s tax numbers were, it should have been a pretty decent production centre but fundamentally wasn’t. Ironically, when South Asia was much poorer, 60-70 years ago, it didn’t show the same trend.

Despite this weak tax base, the region has continued to have seasonal and sometimes continuous fiscal needs. Local agricultural cycles are extremely seasonal and this has meant both a historical tradition and modern mechanism of both fiscal and credit support. The end result? Government expenditure is largely constrained outside of these needs, meaning South Asia actually has a relatively small state sector compared to most regions in the world. It then spends less on human capital than many other parts of the world, with government education expenditure only reaching global averages in India, and massively underspending across the region in government healthcare.

Yet despite this, South Asia’s human capital remains some of its most valuable resources. Personal remittances account for a much larger portion of South Asia’s GDP than most of the world, and at a smaller scale, the same is true for ICT service exports as well. While a lot of this has specific reasons - historical ties to the Middle East on remittances being a key story here - it doesn’t detract from the overall story that despite weak human capital investment, the consumption side of the economy has supported human capital growth nevertheless.

What makes South Asia?

Very few of what I discussed above on its own, is unique to South Asia. Plenty of regions and countries have low taxes, have strong human capital, have high FX needs, are oil importers, have high consumption, have high populations. Yet all of this together? That’s where South Asia becomes unique. Not just at these topline factors but even within these, the combination of all of these working together seems quite distinct to South Asia.

Why is this the case? Perhaps some combination of its cultural, social, and economic history is at play. The specific historical role that the local caste system has played, how it played a critical role in pre-modern and continues to do so in modern trade, the impacts of colonialism, the shape of post-colonial democracy, the constant seasonal impact of the monsoons, all likely played at least somewhat of a role. At this stage, I’m not going to spend too much time exploring these reasons, but merely establishing the distinctness of South Asia as an economic region.

With all of these factors, there are some changes that might be undergoing. Compared to the data at 2019, the post-Covid world seems to have reduced South Asia’s deficits considerably. Global trade is anyway at an interesting place, with at least some changes liely over the next few years. In the meantime, South Asia is getting increasingly interconnected financially. As we go ahead, I think South Asia becomes increasingly and visibly more distinct as an economic region. If South Asia pulls ahead in its GDP growth, its impact on the world will very likely increase markedly. In such a world, figuring out what South Asia is, and how it is distinct will matter.