Understanding credit - the lifeblood of the economy

How banks create money and drive consumption and production

This piece is part 3 of a multi-part series going into the role of money and inflation in Sri Lanka. The first two parts can be found here and here. This piece will focus on how I understand and see credit in the economy, and what it means. This piece is meant to be a precursor to a more detailed dive into how credit works in Sri Lanka, but explaining some ideas behind it in more detail felt easier than cramming everything into one piece alone.

Credit IS the lifeblood of the economy - and I don’t exaggerate when I say this. But that doesn’t make credit a simple good that must always be given - Sri Lanka’s own experience with catastrophic inflation is a good example here. Too much blood in your veins doesn’t help keep you alive in the end.

Understanding the role of credit, in my view, is a critical part of understanding the workings of the economy, and in particular, how inflation moves. For a country going through a period of high inflation (though thankfully, inflation which is slowing down), this becomes especially important.

What exactly do I mean by credit?

Very simply, I mean the amount of loans and debt taken on by the economy overall. This is not just limited to loans taken by individuals, loans taken by the private sector, but also very much includes loans taken by the government and government institutions as well. Credit also includes beyond just simple loan contracts, but also includes tradeable debt like bonds and commercial paper, but also any repo/reverse repo contracts on top of those as well. Of course, the further you go into the financial system and the more derivative credit becomes, the more and more complicated the situation becomes. Thankfully for our purposes, the Sri Lankan system isn’t heavy on the derivative side so anything beyond repos become quite small, and small enough to not be a major factor (at least just yet).

How does credit work - is the theory realistic?

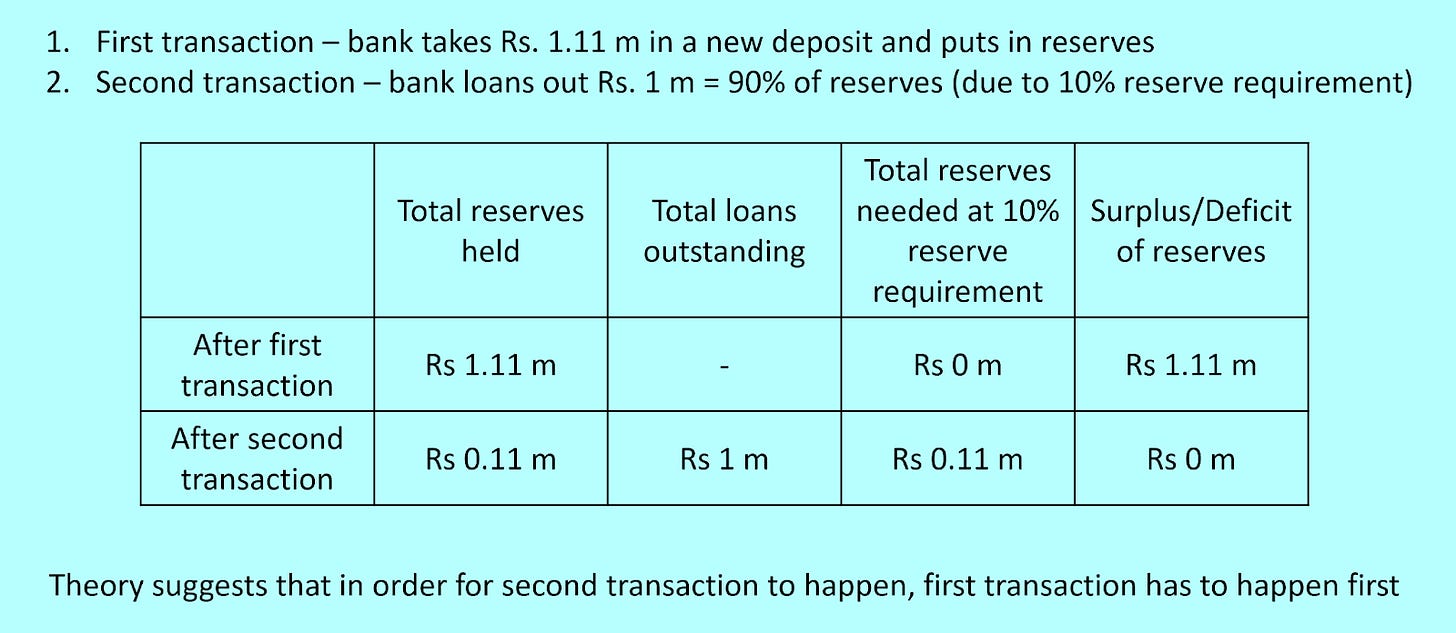

The textbook definition of lending is where a bank or another licensed financial institution takes money in as a deposit (or money from shareholders it keeps as capital), and then lends that money to the economy (after keeping a certain % of the deposit in reserve), and the process repeats.

For example, if a bank has a reserve requirement of 10% and receives a deposit of Rs 1.11 m, it is required to keep Rs 0.11 m in reserve and can lend out the remaining Rs 1 m to other borrowers. The borrowers then deposit that Rs 1 m into another bank, which is also required to keep a fraction of that deposit in reserve and can lend out the rest. This process can continue, leading to a multiplier effect in which the initial deposit can result in many times its original amount being loaned out.

This is the textbook definition of how bank lending works - known as the fractional-reserve theory. I personally believe this remains theoretical only, and that the practical reality of how banks lend is different. In practice, I don’t think it’s accurate that banks loan out money that they have direct deposits for. I’ll give two explanations to show this.

In both of these explanations, lets think of what happens when you go to the bank to get a loan. Assume that the bank has a reserve requirement of 10% and you’ve asked for a Rs 1 m loan to be repaid in 7 years. Lets also assume, of course, that you are creditworthy, the bank has done due diligence, and has decided that YOU are worth giving a loan to. The only thing now they have to deal with is actually giving you the loan.

Firstly, according to the theory, due to the need to match deposits, in order to give this sort of loan, the bank will need Rs 1.11 m (since they can only lend 90% of the deposit amount) in a 7 year deposit (since they’ll have the pay the deposit back in full once the loan is fully paid off). In practice though, will the loan officer start calling around frantically, asking if such a specific deposit was made somewhere, so that they could lend Rs 1 m to you? The simple answer is no. The loan officer isn’t practically matching the deposit to your lending need, at least not at that immediate moment.

Okay, but this could be because the bank already has extra cash so they don’t need to directly match everything. But surely they’re still looking at reserve requirements in close detail? I would argue not immediately.

For the second explanation then. In order to meet reserve requirements in practice, the bank branch you are getting your loan from would need to thereby know the exact amount of reserves and cash held by the bank overall, as well as the total value of loan contracts that has been signed up until that moment. Is it realistic that even a branch manager has direct access to all the most up to date information that the bank’s treasury has, and that they make lending decisions based off that information? I would argue no.

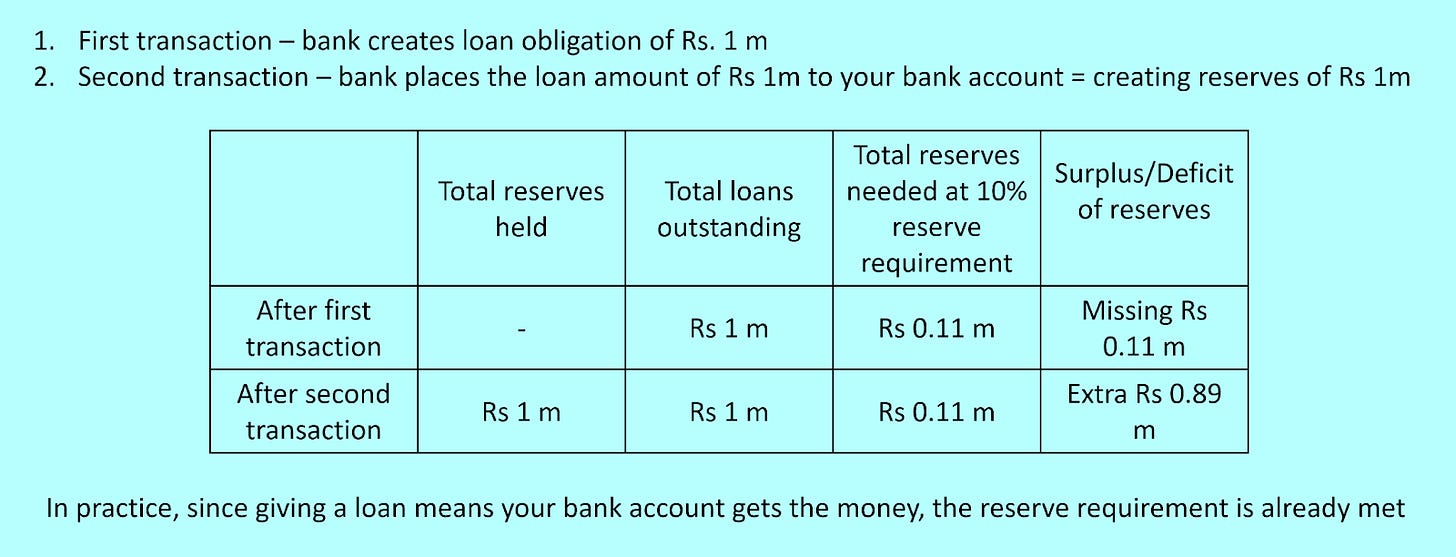

My argument here is that it’s not really practical to strictly follow reserve requirements and deposit matching in a continuous way for every lending transaction as theory suggests, at least not as a factor that the actual bank officers consider before making each and every single lending decision. Of course, reserve requirements still need to be met for sure - so how does this happen?

Credit creation in practice - creating money now, dealing with issues later

My view is that the reality of how credit creation works in many countries of the world, including Sri Lanka, is one where the reserve requirements and deposit matching needs happen in aggregate later, and any short-term needs are met by the banks themselves borrowing from others. Let's explore this view, and use a few diagrams to illustrate this.

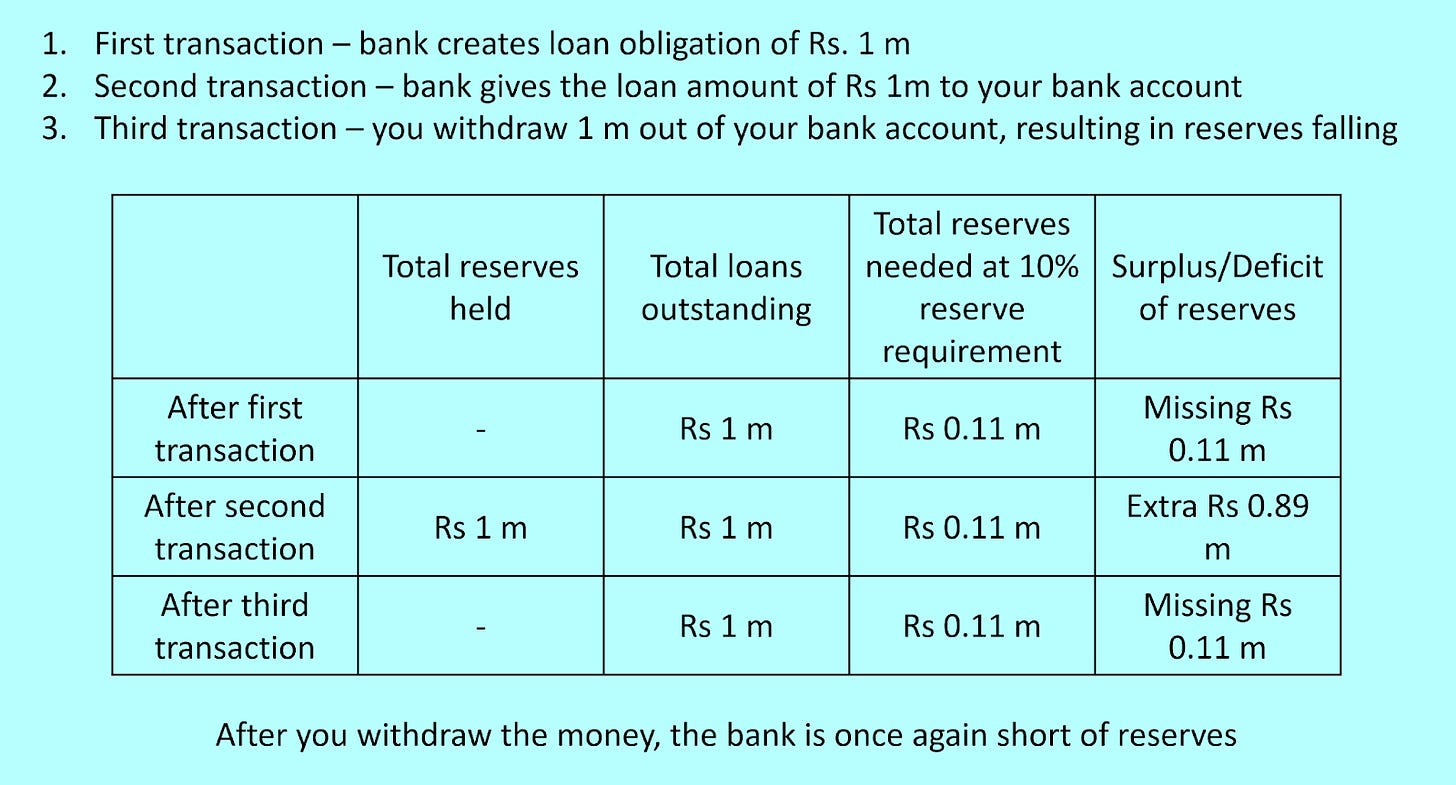

When a bank first extends a loan, what would happen is that they would both see an increase in their loans (an asset since a loan is something that gets paid back to the bank later) AND an increase in deposits (a liability for the bank, since it can be withdrawn as cash or transferred to another account) as the bank puts the loaned money into your bank account. Since in practice, the reserve requirements don’t have to be (and practically can’t) be met every second for every transaction throughout the day, it’s perfectly possible for the bank to essentially create the reserve requirement it needs on their own. This first part is probably the least intuitive - how come a bank creates money out of nowhere? But practically, this is my view on how it works.

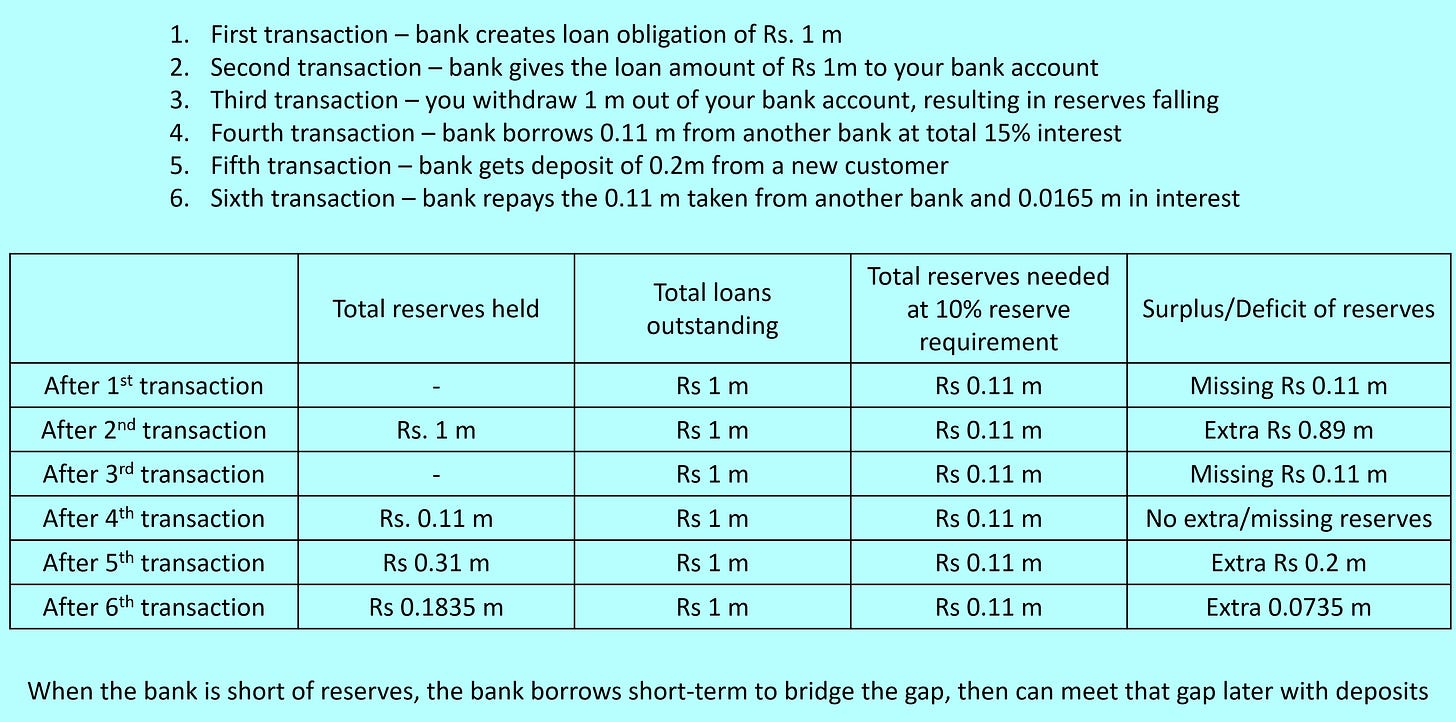

However this is only a short term thing. While it’s technically possible for the bank to just issue a loan, put the loaned money in your account, and then when the loan is due, just take the money back (accounting for interest of course), in reality, you’re not going to leave the money in the account for ever. Most people take loans to use the money, and for that, the money can leave the banks accounts - meaning the increased deposit falls, meaning that in order to meet the reserve requirement, the bank NOW needs some more money.

There are two ways this can happen. First, is by NOW getting a new deposit in (or a sum of deposits that fit the reserve requirement). Second, is for the BANK to take some short-term debt to get some cash and fill the reserve requirement. In practice, my view is that both of these happen - in the short-term, the bank can use short-term borrowings to meet this (for example, borrowing some money from the central bank or from other banks at the end of the day) until they get enough deposits later on. However, if we’re at a place where the bank already has excess reserves, then the need to do new short-term borrowing is limited.

The reality of credit creation affects what causes loans to be extended

Understanding this practical reality is important because it changes whether lending can happen or not. Whereas according to theory, the presence or absence of deposits is a main factor to whether a loan can be given, in this practical framework that isn’t as critical anymore - or at least, isn’t as critical NOW. What’s more critical, is whether short-term borrowings are possible, and at what rate. The more money is available in short-term borrowings and the easier it is to borrow that money, the longer a bank can sustain itself without needing to take on new deposits. Of course, eventually they definitely do - but until that happens, banks have some leeway in practice (the presence of repo markets and derivatives markets help delay that even further, but in countries like Sri Lanka, derivatives in particular aren’t as large a deal, and private repo markets are generally dwarfed by central bank facilities. The process is also a lot more complicated than what I explained, but the simple explanation can be approximated through considering all of these as simple “short-term borrowings” as well).

Beyond this, where the specific credit goes also matters. For example, extending a loan that is used to buy machinery to produce exported textiles is different to a loan that is used to build a house which is different to a loan that is used to buy a Treasury bill with. The first and third will both produce income, though the first is more longer-term and uncertain than the third. The second is very much a consumption decision, so the ability to repay will be different - though if housing prices are rising, someone could build the house, sell it off, and then easily repay the loan. These types of differences also directly (in terms of repayment ability) but also indirectly affect how credit is created (in terms of overall amount of money in the economy that is used to both meet the deposit requirements but also short-term borrowing ability of banks).

This story and explanation then affects how inflation can work. Instead of needing to strictly match deposits, banks can create more credit since the short-term reserve requirements can be met through short-term borrowing, and then the bank can get deposits later (often, because the initial loan given could create additional income in the economy, which can return to the bank as a deposit later). If the credit created was used for consumption, then there is a greater inflationary effect in the economy than otherwise possible. On the other hand, if the credit created was for production, then there could be a greater deflationary effect than otherwise possible.

The whole story for countries like Sri Lanka also depend on the role of depreciation, given the large import dependency. This story ties in from the credit angle, so that’s what we’ll go into next - how credit has expanded depreciation tendencies in the Sri Lankan economy.