The three monetary orders of the dollar system

When a tree falls in the Bretton-Woods, everyone hears it

(This article is one of a multi-part series exploring the global monetary system - starting from its past, and hopefully exploring its future. The first piece - on the dollar’s 8 decade hegemony is here. While some ideas are reflective of standard monetary history, the framing of others are ones that might be a bit new. While I’m sure others have come across similar framing of their own, what I put here is mine - so any errors mine. I have referred to others wherever possible.)

It’s almost become the mainstream view, that the world’s economic order is changing. Looking back, one might argue that this has been happening for a while, though this was slow and gradual enough that the prophets of orthodoxy could claim otherwise. Now, with the rapid shifts happening alongside the new Trump administration, even the most hardened critics of change will have to agree that things are moving pretty dramatically.

What does this change look like? One aspect is that of the monetary system itself. In a previous article, I spoke through why I think the dollar’s dominance over the last 80 years can be understood as a function of the depth of USD markets, but that the cost of ths is the credit expansion and deficits that follow the use of these markets. That was what I see as having underpinned the USD as the global reserve currency.

However, although the USD has been the reserve currency for at least the last 8 decades, the monetary system underpinning this has changed in my view. The obvious part of this is the Bretton-Woods system and the post-Bretton-Woods world order, but I think its better understand as three, roughly 25 year periods instead.

1. The Bretton-Woods monetary order

The first monetary order of the modern dollar was under the Bretton-Woods. In short, this was where the currencies of the world would peg against the USD, and the USD would peg against gold. There are plenty of reasons behind this decision, but I think for this story, the critical one is that the world wanted to avoid competition in exchange rates and the capital flow speculations that followed. By setting a globally agreed system in place, you can avoid countries competing against each other to attract foreign capital through devaluation of their currencies.

Of course, this system only worked as long as the US held the ability to maintain parity with gold. If the global system wanted a roughly constant amount of dollars, or if the amount of gold held by the US rose alongside any new USD demand, this would work. But in reality, the “strength” of the USD, backed up at the start by plenty of gold, meant countries, businesses, and individuals started racking up USD-based liabilities. These future requirements for USD meant that the US slowly had to give more USD than it could currently create parity for, to the world.

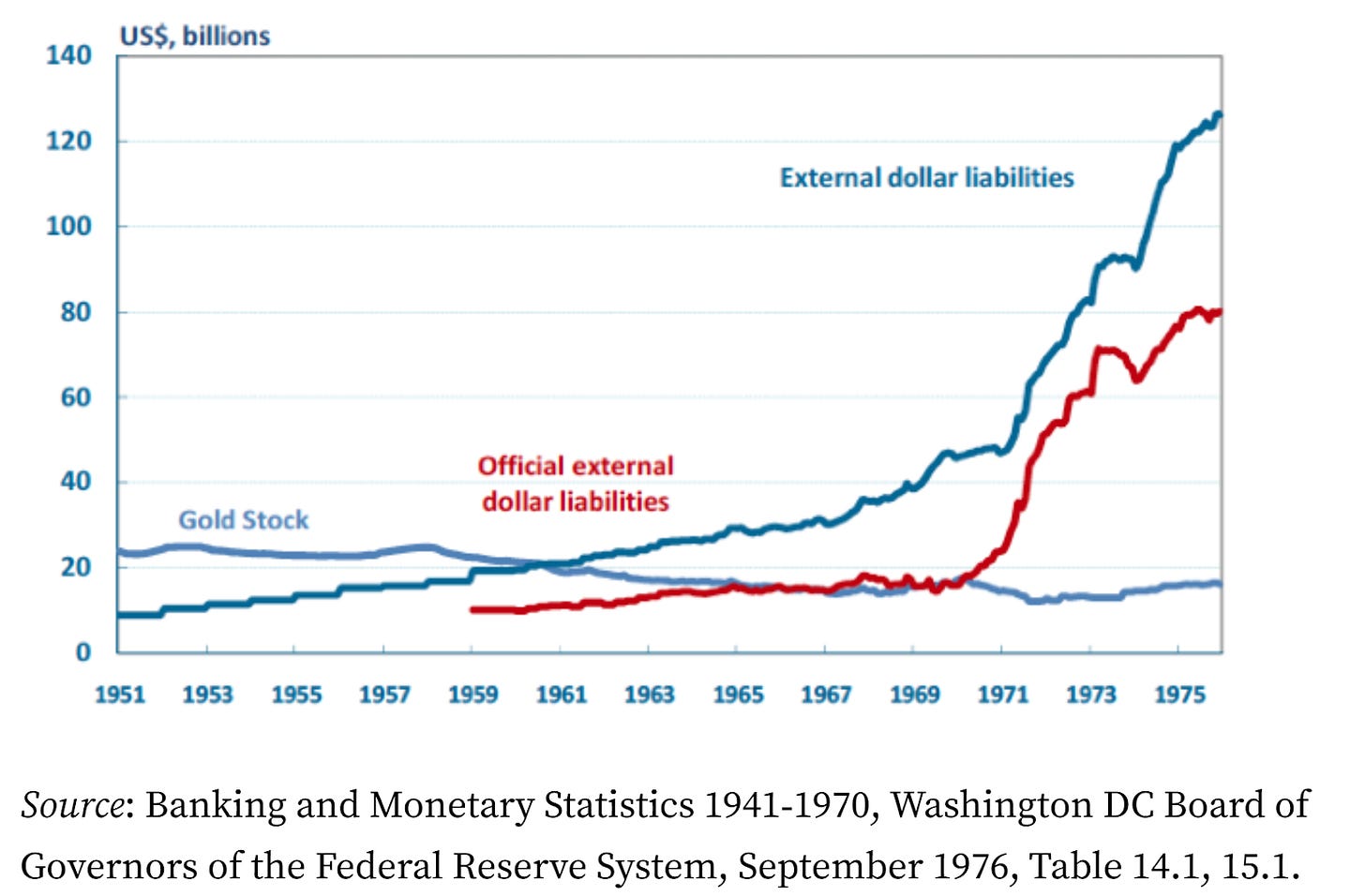

As long as the US had spare dollars of its own, built up by external surpluses, this was fine. The US would be able to lend these dollars to anyone who wanted them. But countries that got these dollars now had to do something with them. Some, like Italy, spent it more on consuming the products of American production than in creating their own production. For others, the benefits of having extra USD meant they invested in their own production. Now, they have their own ability to produce, and need someone to buy their products. The US, with its strong economy, was the obvious choice. They could easily fund that consumption through credit as well - after all, countries that now had surplus dollars could lend to the US anyway. In the chart below sourced from CEPR, you can see how dollar liabilities exceed the American gold stock in the early 60s - the point at which this changed.

But this meant the US had to keep running deficits AND other countries needed to keep running similar surpluses to lend to keep the US running. This was the Bretton Woods monetary order in a nutshell - cycling USD between the US and the rest of the world, all the while keeping the (increasingly nominal) peg to gold. Running so many deficits then means that conventionally, the system should eventually “fail”. Debt rises faster than growth, and eventually, the likelihood that either the US has enough dollars or the world produces enough products to finance the US both fall.

2. Post-Bretton Woods multi-surplus monetary order

Eventually, the Bretton-Woods system collapsed as the demand for dollars exceeded the ability of the US to maintain parity with gold. After a 1971 devaluation of the dollar, the US managed to stabilize its external accounts for just a tiny bit, before rising oil prices and then later, offshore credit growth meant the US returned to even larger deficits.

Rising oil prices could even be understood (somewhat controversially) as a result of the US devaluation. The shock it created across the world could easily have affected supply dynamics in the Middle East. Regardless of whether this was the case, rising oil prices meant massive surpluses by the petrostates of the Middle East. What could they do with this money, but park it somewhere?

The outcome of this - both directly through the petrocurrency agreements of the 70s and indirectly by boosting liquidity across the world from the 80s - was that you had a lot of money willing to lend into the US. The US borrowing this money, using it domestically to buy foreign goods and services, that money being accumulated by trade partners that relent it to the US was the core part of this part of the monetary system.

This cycling of money might sound similar to Bretton Woods but the major difference was that global currencies were no longer fixed. They moved dramatically if needed, but even steadily otherwise. This movement meant that across this period, you had varied countries and varied players combined lending into the US. There was no singular counterparty to the US deficits across this period. In the 70s, the petrostates covered most of it. The early 80s had rising Japanese surpluses, and the late 80s had the European surpluses really kicking up, and then East Asia rising across the 90s.

This multi-surplus monetary order had one big consequence - money rushing in and out across the players. At varied points, even countries with small surpluses mattered more to the overall balance - so capital moved all over. The cost of this was visible in the massive currency flows out of Latin America in the 80s in particular, and Asia in the late 90s. But by the late 90s, one player became increasingly and clearly the counterparty to the large deficits and started changing this multi-surplus monetary order to a more straightforward uni-surplus order - China’s integration into world trade.

3. The US-deficit and China-surplus monetary order

The monetary order that was clearly visible in the early 2000s but likely was starting to be in play from the mid to late 90s, was when East Asia, and particularly China started to run massive surpluses on their external account and using the proceeds of these to financing the deficits in the US. The mechanism here was the same as in the previous monetary orders, but with a single counterparty to the large deficits of the US, the dynamics were different.

This single counterparty status didn’t really materialize until around the mid-2000s, but the trend was starting from the mid 90s anyway. As East Asia rapidly industrialized, they started gathering larger and larger FX surpluses. For countries that were still, largely poor, the deployment of these surpluses had to go somewhere - and eventually ended up in the US deficit.

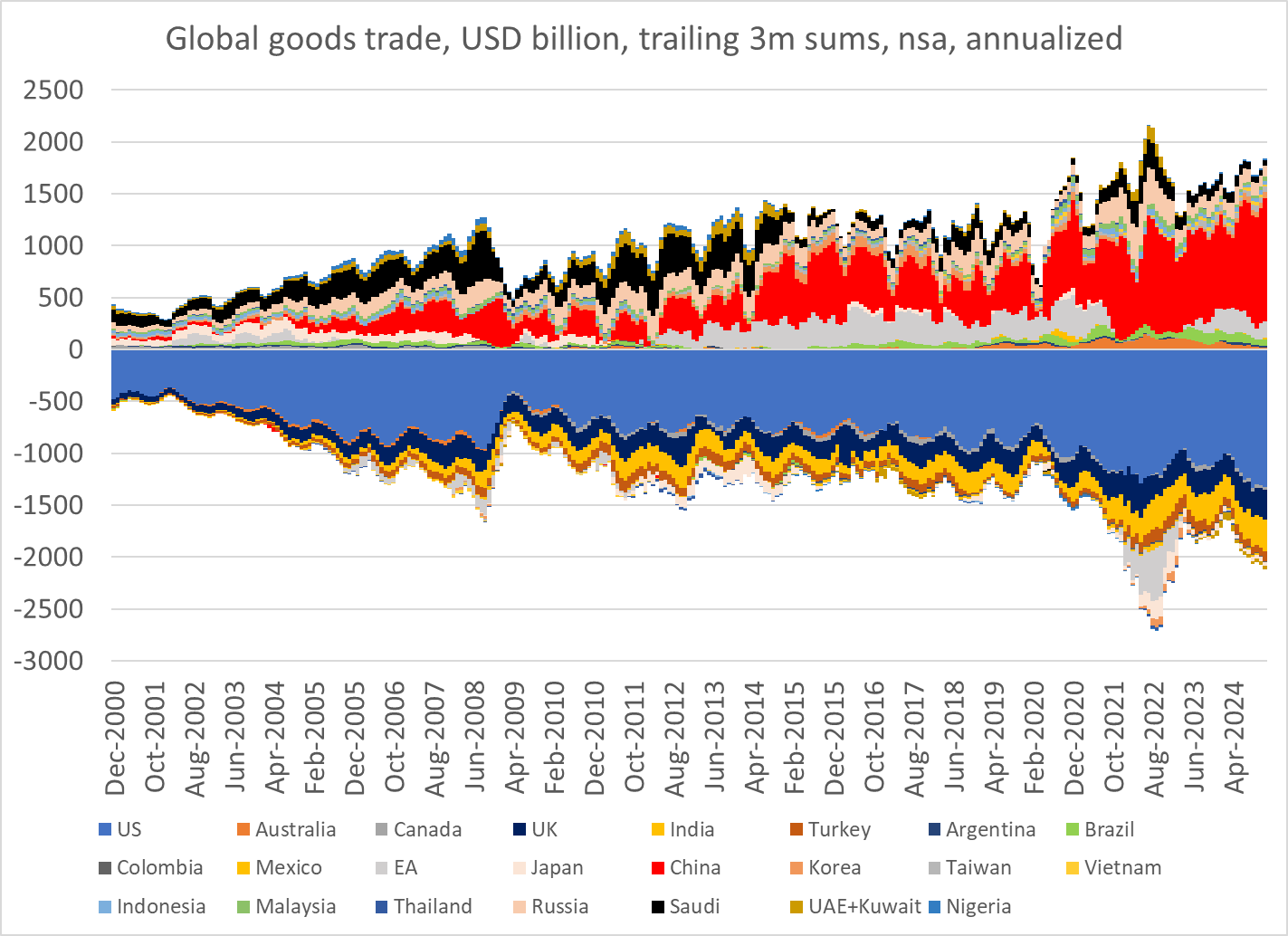

However, as China became the main player in this story, the dynamics change. It is no longer varied countries with varied domestic and international priorities, and exposed to varied volatilities that provided this surplus. It was China, singular and consistent. As opposed to the volatilities of the multi-surplus system, you had some level of stability. As long as the system functioned, the system was largely stable. The US ran deficits, paid China to produce goods, which then invested that money back in US treasuries. The chart below from Brad Setser’s shows how this has evolved.

This translation of Chinese surpluses to US deficits doesn’t need to be direct. Since the mid 2010s, China has actually been reducing it’s holdings of US treasuries. This has only accelerated since the pandemic. Yet American deficits grow as do Chinese surpluses. How? Through intermediaries (who might not even know they’re acting as such!). As long as the two end up meeting each other at some point, the two balance against each other.

Yet even uni-surpluses have large impacts. As opposed to the relatively more local impacts of a multi-surplus order, the uni-surplus system builds up to much larger levels. At those points, any shifts can be pretty dramatic in their impacts. These could be local too - China’s rapid rise as a cheap industrial power clearly hit Germanic Europe’s production power negatively. But the bigger impacts that matter are global. What happens when the system keeps going and both sides end up having far too much pressure to go on?

What will the next monetary order be?

If we assume that roughly 25 year cycles exist for monetary orders, we’re right around the cusp of another shift. Visibly, that seems obvious too. American trade contraction and European rearmament are the obvious and visible parts of this. But China has continued to struggle on its consumption boom, other than the success of moving low-consumption rural Chinese to less-low-consumption urban Chinese.

But what will this next shift look like? Here, I think we can go even deeper into the way these monetary orders have worked in the past. Each of these orders have had what feels like specific periods within that are distinct. Perhaps this can help us figure out the changing world.